The Development of Competition Aerobatics

Almost as soon as people had flying machines they started experimenting with them. Russian pilot Petr Nesterov and Frenchman Adolphe Pégoud flew the first loops in 1913, and by the end of the first World War battle-hardened fighter pilots had a wide repertoire of attack and escape manoeuvres to manage their enemies. Soon after this they were looking for ways to keep flying, and a natural solution lay with barnstorming and air-shows. Elaborating on their ingrained combat manoeuvres they experimented to discover what an aeroplane could really do.

Almost as soon as people had flying machines they started experimenting with them. Russian pilot Petr Nesterov and Frenchman Adolphe Pégoud flew the first loops in 1913, and by the end of the first World War battle-hardened fighter pilots had a wide repertoire of attack and escape manoeuvres to manage their enemies. Soon after this they were looking for ways to keep flying, and a natural solution lay with barnstorming and air-shows. Elaborating on their ingrained combat manoeuvres they experimented to discover what an aeroplane could really do. The question "who of us is best" was asked early on, and before long aerobatic competitions became an established sporting pursuit.

The question "who of us is best" was asked early on, and before long aerobatic competitions became an established sporting pursuit.

Through a century of continuous evolution, aerobatic competition flying has now developed to provide a fascinating and compelling aerial motor-sport that combines the precision and formalism of figure skating with the technical demands and sophistication of motor racing, while mastering an intellectual challenge something like a high-speed 3-dimensional version of chess. These flights are conducted in powerful machines that pilots must fly within a strictly defined 1km "box" of air in front of the judges at hundreds of mph, undergoing positive and negative G-forces higher than those of a fighter jet. This is a stressful and challenging requirement, rarely achieved with the accuracy and artistry sought.

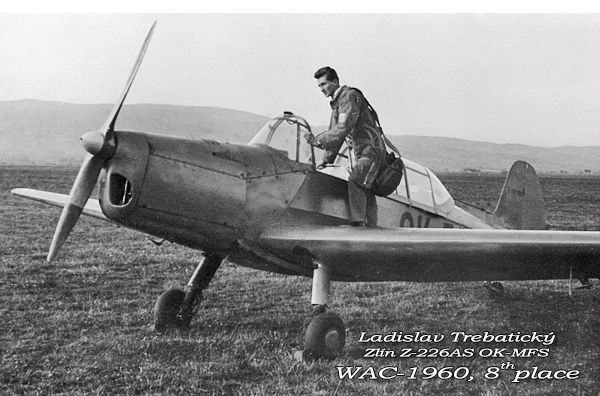

For many years success at such contests relied largely upon entirely subjective assessments, based on each observer’s personal impression of the flight. Various attempts were made to standardize the scoring format, the World Cup of Aerobatics at Vincennes, Paris in 1934 and the UK’s Lockheed Trophy through the 1950’s being perhaps those most dedicated to ‘free expression’, but none really lasted. In 1960 the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) established its aerobatic commission CIVA with the first World Aerobatic Championship, and a reliable approach to scoring became critical. At that inaugural WAC in Bratislava, won by Ladislav Bezák in a Zlín 226, it became clear that a standardised system was necessary to define exactly what each pilot intended to fly. In 1961 a new system created by Spanish aerobatic ace Colonel Jose Luis de Aresti was adopted by FAI, formally categorising the figures so that aerobatic flights could be judged and graded in order to produce fixed numeric scores. Based on his "Sistema Aerocriptographique" notation, this grouped aerobatic manoeuvres into families of figures that could be assembled to create sequences of clearly defined figures that pilots would fly and, critically, judges could read from their marking sheets to assess the execution of the figures and award appropriate grades.

For many years success at such contests relied largely upon entirely subjective assessments, based on each observer’s personal impression of the flight. Various attempts were made to standardize the scoring format, the World Cup of Aerobatics at Vincennes, Paris in 1934 and the UK’s Lockheed Trophy through the 1950’s being perhaps those most dedicated to ‘free expression’, but none really lasted. In 1960 the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) established its aerobatic commission CIVA with the first World Aerobatic Championship, and a reliable approach to scoring became critical. At that inaugural WAC in Bratislava, won by Ladislav Bezák in a Zlín 226, it became clear that a standardised system was necessary to define exactly what each pilot intended to fly. In 1961 a new system created by Spanish aerobatic ace Colonel Jose Luis de Aresti was adopted by FAI, formally categorising the figures so that aerobatic flights could be judged and graded in order to produce fixed numeric scores. Based on his "Sistema Aerocriptographique" notation, this grouped aerobatic manoeuvres into families of figures that could be assembled to create sequences of clearly defined figures that pilots would fly and, critically, judges could read from their marking sheets to assess the execution of the figures and award appropriate grades.

While the Aresti system has evolved over time, its introduction was a key step in regularising aerobatic competition and making the judging process more reliable, though inevitably it remains based upon the perceptions and opinions of a panel of experienced judges. It defines for each figure a precise path through the air, the competitor's aim being to demonstrate the accuracy of the flight-path and the attitude of their aeroplane to the panel of judges on the ground. Each judge grades only what they see, and herein lies the very heart of the matter. The judge starts every figure with a perfect 10 in his head; each detected error leads to a deduction – 5 degrees off heading, deduct 1 point; start a loop with less than a perfect arc, deduct 1 point; roll 10 degrees too far, deduct 2 points, and so on. Each figure in the Aresti catalogue has a difficulty or "K factor"; multiply it by the average of the judges’ grades to calculate the final score for the figure. For a simple loop the K factor is just 10, while for a more complex figure it can be as high as 50 or 60, as the example sequence below shows. In reality, it is almost impossible to achieve a maximum score for even the basic loop.

While the Aresti system has evolved over time, its introduction was a key step in regularising aerobatic competition and making the judging process more reliable, though inevitably it remains based upon the perceptions and opinions of a panel of experienced judges. It defines for each figure a precise path through the air, the competitor's aim being to demonstrate the accuracy of the flight-path and the attitude of their aeroplane to the panel of judges on the ground. Each judge grades only what they see, and herein lies the very heart of the matter. The judge starts every figure with a perfect 10 in his head; each detected error leads to a deduction – 5 degrees off heading, deduct 1 point; start a loop with less than a perfect arc, deduct 1 point; roll 10 degrees too far, deduct 2 points, and so on. Each figure in the Aresti catalogue has a difficulty or "K factor"; multiply it by the average of the judges’ grades to calculate the final score for the figure. For a simple loop the K factor is just 10, while for a more complex figure it can be as high as 50 or 60, as the example sequence below shows. In reality, it is almost impossible to achieve a maximum score for even the basic loop.

The pilot’s task is therefore to fly the sequence of figures so they appear perfect to the observer on the ground. However not only is the aeroplane moving but so is the air itself, in the same way that a strong tide affects the path of a small boat; these influences are, of course, unknown from the perspective of the judging panel far below. Flying a high-performance machine in such a dynamic environment, working to locate and shape the figures accurately so the judge sees only perfectly straight lines, precisely shaped looping segments, consistent rolls, flicks and spins is a tantalisingly difficult business.

The technical sophistication of the machinery has evolved significantly too. Modern aerobatic aircraft are astonishingly strong and surprisingly light. In the Unlimited class, the top level of competition, both aeroplane and pilot are frequently subjected to +10 and -10 times the force of gravity, sometimes more. By the standard of a normal pilot the control response is extreme, a roll-rate higher than 400 degrees/sec being common. For competition flying however stopping the roll precisely, within a degree or two of the intended angle, is critical to get the marks sought.

The technical sophistication of the machinery has evolved significantly too. Modern aerobatic aircraft are astonishingly strong and surprisingly light. In the Unlimited class, the top level of competition, both aeroplane and pilot are frequently subjected to +10 and -10 times the force of gravity, sometimes more. By the standard of a normal pilot the control response is extreme, a roll-rate higher than 400 degrees/sec being common. For competition flying however stopping the roll precisely, within a degree or two of the intended angle, is critical to get the marks sought.

The intellectual challenge takes several forms, most clearly represented in the idea of "Unknown Sequences". Aerobatic competitions are structured as a series of flights, the first of these with some or all of the figures “Known” where the pilot can spend much time in prior training sessions learning how to fly them well. The following programmes, however, are usually "Unknown” sequences the pilot will not have seen before, composed at the event from figures submitted by teams or individual pilots and flown for the first time in front of the judges. These can be extremely challenging to learn and mentally rehearse so that, when eventually in charge of the aeroplane, each figure can be well presented and accurately placed and, hopefully, the judges will see what they want and award good marks.

At domestic contests, Club and Sports levels or their local equivalent provide the initial entry stages, whereas international championships start at the "Intermediate" level for pilots of moderate aerobatic experience. Next up is the "Advanced" class for more experienced aerobatic competitors, whose capabilities will have been developed through many hours of training and competition. The "Unlimited" category is of course for the best pilots in the world, where a top-class aeroplane is essential and the physical stresses and complexity of the figures demand extremely high levels of experience, skill and commitment.

At domestic contests, Club and Sports levels or their local equivalent provide the initial entry stages, whereas international championships start at the "Intermediate" level for pilots of moderate aerobatic experience. Next up is the "Advanced" class for more experienced aerobatic competitors, whose capabilities will have been developed through many hours of training and competition. The "Unlimited" category is of course for the best pilots in the world, where a top-class aeroplane is essential and the physical stresses and complexity of the figures demand extremely high levels of experience, skill and commitment.

This extraordinary sport is open to club flyers who like to push themselves a little at the weekend, all the way up to the best pilots in the world, some of whom dedicate their lives to achieving excellence. The structured progression in competition classes offers a highly rewarding route for pilots to acquire new skills and grow their experience. Even as a private pilot with a PPL you can learn enough to take part in aerobatic competitions with a club aeroplane in a few weeks, then spend a lifetime and never be perfect.

Dave Farley

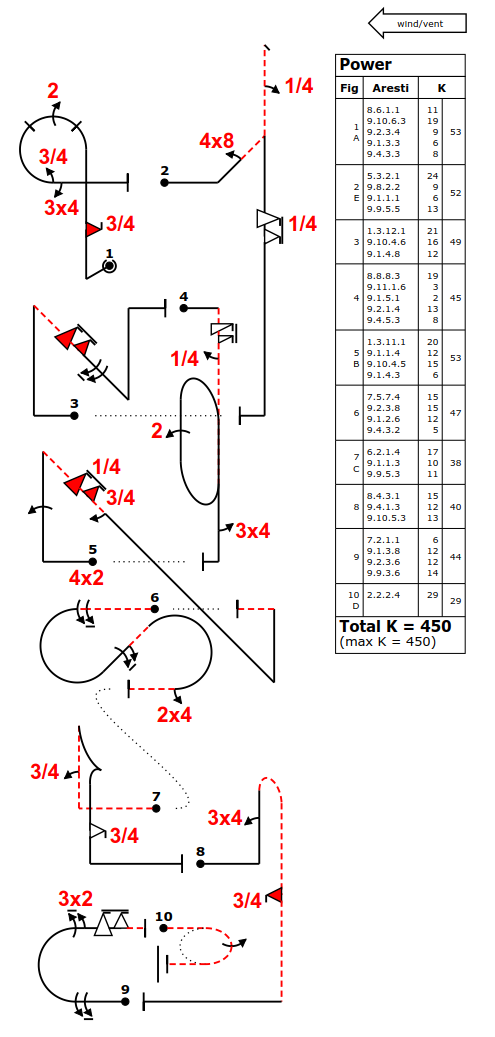

Typical example of a 2021 Unlimited power Programme-1 ten figure "Free Known" sequence

Cross-box dive to gain sufficient entry speed for Figure-1, wing rocks to alert the judges ... then -

Figure 1

Pull vertical with short line to ¾ negative flick roll, extend the line (same length again) then pull downwind into three-quarter loop with 2-point roll at the top, when level ¾ roll and opposite 3x4 rolls, exit erect into wind. End.

Figure 2

Pull 45° into line with central 4x8-point rolls, push vertical with ¼ roll into stall turn, on the down-line centrally placed 1¼ positive flick roll, pull downwind to erect exit. End.

Figure 3

Pull vertical plain line, pull down to 45° inverted into 1½ negative flick with opposite double roll, pull vertical into plain line, exit into wind erect. End.

Figure 4

Erect spin into double Humpty Bump: spin is 1½ turns then opposite ¼ roll, line to positive half loop into vertical up with 2x2 rolls, positive half loop into 3x4 rolls down, pull erect downwind. End.

Figure 5

Pull vertical into line with central single roll, pull down to 45° inverted line with 1¾ negative flick and opposite ¾ roll, pull vertical into plain line, pull to exit inverted downwind. End.

Figure 6

Four ½ rolls into pull ⅝ loop, on the 45° up-line 1½ roll to inverted, followed by ⅝ pull loop with 2x4 rolls when level, exit inverted downwind. End.

Figure 7

Push vertical into ¾ roll up, then canopy-up tail-slide with ¾ positive flick on the down-line, pull erect into wind, exit. End.

Figure 8

Pull vertical into 3x4 rolls, line up to push-humpty half-negative loop top, ¾ negative flick on the down line, pull erect downwind. End.

Figure 9

Double roll into pull half-loop upwards, at the top 3 half-rolls into same direction 1½ positive flick roll, exit inverted into wind. End.

Figure 10

180° inverted entry rolling turn with one roll outwards, exit inverted downwind. End, end of sequence.

Wing rocks ... land.

Are you hosting an aerobatic event?

Our aim is to provide forward information for everyone with an interest in aerobatic competition flying.

For this however we do need your help, so please make sure that your Aerobatic Club or National Airsport Control sends us details of all competitions that are open to pilots and/or judges from other countries and we’ll add them to our Championship Calendar so that they get the widest circulation possible.